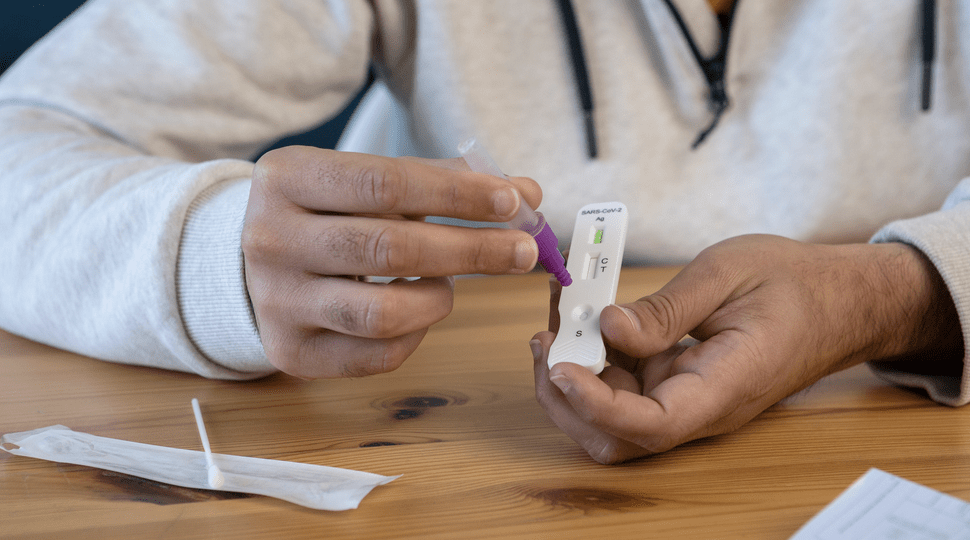

Numerous diagnostic test producers have created and started selling quick and simple-to-use devices to assist testing outside of laboratory settings in response to the escalating COVID-19 epidemic and limitations of laboratory-based molecular testing capacity and reagents. These straightforward test kits are based either on the detection of COVID-19 viral proteins in respiratory samples (such as sputum or throat swabs) or on the identification of human antibodies produced in response to infection in blood or serum.

What is a Rapid Antigen Test?

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) detect the presence of viral proteins (antigens) expressed by the COVID-19 virus in a sample from the respiratory tract of a person. One study examined trials using five paired nasopharyngeal swabs and saliva samples and reported diagnostic accuracy for SARS-CoV-2 detection in a systematic review and meta-analysis. The main finding of relevance was the variation in sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 detection between saliva samples and nasopharyngeal swabs. The reference standard was a positive result with either sample. Because it was assumed that any positive result was accurate, specificity could not be assessed. According on the age, the existence of symptoms, the study environment, the method of saliva collection, the analytic form, and the use of transport medium, subgroup analyses evaluated differences in sensitivity.

A total of 37 trials with 7,169 participants and 7,332 paired nasopharyngeal swabs and saliva samples were included. 2,327 people, or 32%, tested positive for either saliva or nasopharyngeal swab. In comparison to nasopharyngeal swab testing, the overall sensitivity for salivary testing was 3.4 percent lower (95 percent confidence interval [CI], -9.9 percent to +3.1 percent). The combined sensitivity for testing saliva was 86.9%. (95 percent CI, 82.3 percent -90.4 percent ). The changes in sensitivity between salivary and nasopharyngeal tests ranged from -9.3 percent to +1.5 percent, with no significant differences seen in stratified analyses.

The sensitivity of sample collection using a nasopharyngeal swab or saliva did not significantly differ. However, the salivary collection is far less expensive.

Beyond the annoyance of a frontal lobe tickling, collecting nasopharyngeal samples for SARS-CoV-2 has additional difficulties that call for a competent medical expert and personal protective equipment. The SARS-CoV-2 test is simple to perform and may be self-administered anywhere, making it suitable for serial testing. Salivary sample collection seems to be a viable and more economical alternative to nasopharyngeal swabbing and can assist increase testing as SARS-CoV-2 testing is now more frequently required for travel and other purposes.

This sizable meta-analysis supports findings from earlier research that salivary sample collection is probably similar to nasopharyngeal swabbing in terms of sensitivity. Before they may be recommended, these tests must first be authorized in the appropriate contexts and populations. Inadequate testing may hinder efforts to stop the spread of disease by failing to identify individuals with active illnesses or incorrectly diagnosing healthy people as having the illness.

WHO now only suggests employing these cutting-edge point-of-care immunodiagnostic tests in research settings based on the data that is currently available. They shouldn’t be used in any other situation, including clinical decision-making, until there is proof that their use is beneficial for a specific indication.

- Rapid diagnostic tests based on antigen detection

- The current noninvasive gold standard diagnostic test is nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which uses a nasopharyngeal sample. Nasopharyngeal testing cannot be performed in all populations with ease or reliability due to the need for skilled staff and the use of a specialized swab (eg, children and quarantined individuals).

- After a few variations, researchers are once more debating whether nasal swabbing is the most effective method for promptly and reliably detecting Omicron.

One kind of rapid diagnostic test (RDT) looks for viral proteins (antigens) produced by the COVID-19 virus in a sample taken from an individual’s respiratory tract. Target antigen will bind to particular antibodies fixed to a paper strip contained in a plastic casing if it is present in appropriate proportions in the sample, and after 30 minutes will produce a visually discernible signal.

Such tests are most effective in detecting acute or early infection because the antigen(s) detected is only expressed when the virus is actively replicating. Another, more popular kind of quick diagnostic test for COVID-19 is on the market; this test looks for antibodies in the blood of persons who are thought to have the disease. After virus infection, antibodies start to develop over the course of days to weeks. Age, nutritional state, the severity of the disease, certain drugs, and immune-suppressing infections like HIV all affect how strong the antibody response is. Weak, tardy, or nonexistent antibody responses have been described in some individuals with COVID-19, a disease identified through molecular testing (such as RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction).

This means that a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection based on antibody response will frequently only be possible in the recovery phase when many of the opportunities for clinical intervention or interruption of disease transmission have already passed. Studies suggest that the majority of patients only develop antibody response in the second week after the onset of symptoms. Other infections, such as other human coronaviruses, may also cross-react with COVID-19 in antibody detection assays. could produce falsely favorable outcomes. Finally, it has been questioned whether RDTs that detect antibodies can determine a person’s immunity to re-infection with the COVID-19 virus. There is currently no supporting evidence for this.

In order to support the development of vaccines, as well as to advance our knowledge of the extent of infection among people who are not yet identified through active case finding and surveillance efforts, the attack rate in the population, and the infection fatality rate, tests to detect antibody responses to COVID-19 will be essential. However, because they cannot accurately identify acute infections to guide the necessary activities to choose the best course of therapy, such tests are of limited use for clinical diagnosis. When molecular testing was negative but there was a strong epidemiological association to COVID-19 infection and paired blood samples showed rising antibody levels, some clinicians have used these tests for antibody responses to make a presumptive diagnosis of recent COVID-19 disease.

What’s Known So Far

Two unpublished, small sample size pre-print studies presented a preliminary case for saliva testing by swabbing the mouth or back of the throat. The nasal rapid antigen test did not detect positive infections in the 30 individuals with current Omicron infections screened daily with a nasal swab and saliva rapid antigen test until about a day after a saliva PCR test did.

This pre-print implies that nasal quick antigen testing may not detect Omicron at its most infectious stage, despite the fact that it has already been demonstrated that PCR tests detect COVID-19 at a lower threshold than a rapid antigen test. Based on 67 Omicron and Delta cases, another recent pre-print from South African researchers hypothesized that positive saliva tests for Omicron were more trustworthy than positive nasal mid-turbinate swabs. In contrast to Delta, where results from nasal swabs were more reliable than those from saliva swabs. When compared to Delta, Omicron shed viruses more frequently in the mouth than the nose.

Patients coughed three to five times, swabbed their gums and hard palates, and inside of their cheeks, above and below the tongue. A composite was used as the benchmark for comparison, and an infection was deemed to be present if either the saliva or mid-turbinate swab tested positive.

Variation Between Tests

But it’s crucial to comprehend what kinds of specimens these tests gather in order to comprehend why testing from various bodily areas may produce disparate outcomes. The epithelial cells that line the mouth and throat are identical. They differ slightly from the lining of the nose and nasopharynx, though. While nasal swabs mostly collect the virus from respiratory epithelial cells, throat swabs and saliva tests—taken either by spitting in a cup or swabbing the inside of the mouth—collect the virus more from squamous epithelial cells. Tissue tropism, the term used to describe which type of cell a virus “prefers,” seems to be narrower for Omicron than for earlier forms.

Conclusion

The fundamental guidelines haven’t changed much since omicron first appeared, despite the introduction of new sub-variants: according to medical experts, someone can quit isolating after five days if they haven’t had a fever for 24 hours and are showing signs of improvement.

It’s crucial to highlight that, despite some nations modifying national guidance on this, WHO continues to advise that vaccinated people who have COVID-19 symptoms or those living in touch with someone who has COVID-19 should still exercise caution when interacting with others in public.

Some researchers have opposed these regulations, citing evidence that suggests some individuals may continue to be contagious after day five. And many professionals advise delaying your outing until you receive a negative result from an at-home test.

However, if you feel fine, waiting can be annoying, especially if you belong to the group of people who test positive after 10 days.

0 Comments